CRISPR Methods

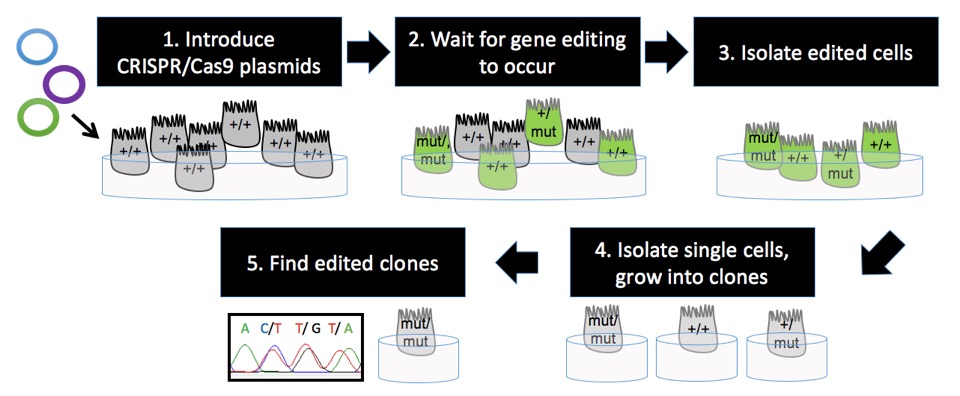

Here’s how the CRISPR/Cas9 system is used to gene-edit cells in culture:

- Introduce the CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids into cells

- Wait for gene-editing to occur

- Isolate cells most likely to be edited

- Isolate single cells and grow them into clonal populations of cells (aka. clones)

- Find clones with the desired edit

1. Introduce the CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids into cells

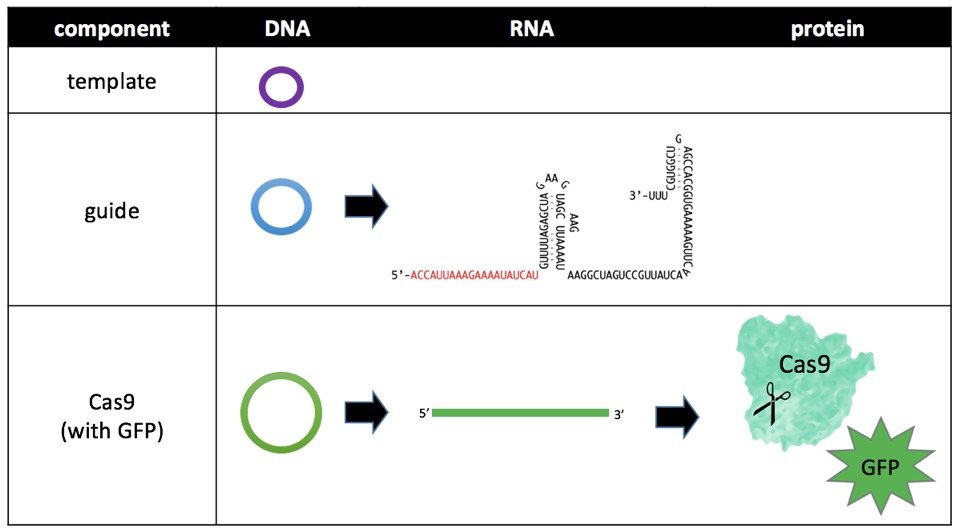

There are three components of the CRISPR/Cas9 system: templateDNA, guideRNA, and Cas9 protein. Notice all three components of the central dogma of biology: DNA, RNA, and protein. Of these, RNA is difficult to work with because it is unstable at room temperature (and cells cannot survive long in the cold) and protein is so large that it is difficult to get past the cell membrane. DNA, however, is easy to introduce into cells. Therefore, all three components are introduced into the cells as circular DNA sequences called plasmids. Plasmids encoding Cas9 are available off-the-shelf, but plasmids for templateDNA and guideRNA are custom designed [link to cloning protocols page; footnote on the protocol’s page: an authoritative source of molecular cloning techniques is Molecular Cloning, A Laboratory Manual; list SnapGene as a resource].

Once the plasmids are available, they are introduced into cells using a process called transfection. Lipofection [link to lipofection protocol] is a common transfection method. Basically, the plasmids are enclosed in vesicles, the vesicles fuse with the cell membrane, and the plasmids are released into the cytoplasm.

2. Wait for gene-editing to occur

Once inside the cell, natural cellular processes turn plasmid DNA into RNA and protein. When guideRNA and Cas9 protein bind to one another and to genomic DNA, the genomic DNA is cut. The cellular DNA repair pathway may use the templateDNA to repair the break, thereby introducing the desired edit.

3. Isolate edited cells

Of the many cells transfected with CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids, 1-90% of cells may actually be edited. The transfection process is often the limiting step in editing: most cells that take up plasmids are edited. A marker protein is often used to identify cells that take up plasmids. With the green fluorescent protein (GFP) marker, for example, cells that fluoresce green are separated [link to FACS protocol] from non-fluorescent cells. Marker proteins can be encoded on the same plasmid as the Cas9 DNA sequence.

4. Isolate single cells and grow them into clonal populations of cells (aka. clones)

The edited cells will have a number of different edits. If the desired edit it the addition of the sequence CTT, then the actual edits might look like this: insertion of CTT, CT, C, or T OR deletion of 1-3 base pairs of the original sequence OR a combination of insertions with deletions. Also, remember that there are two copies of most genes in healthy cells, so the edit may appear homozygous (on both copies) or heterozygous (on only one copy). The situation can get even more complicated in cultured cells, which can have more than two copies of a gene.

The goal is to get a bunch of cells with only the desired edit. First, single cells are isolated from the “mixed population” of edited cells. Next, the single cells are plated individually. Given the right conditions [link to experiment: optimization of single-cell cloning in Calu3], the single cells divide into a “clonal population” or “clone” of cells, all of which contain exactly the same genomic edit(s).

5. Find clones with the desired edit

The DNA from each clone is sequenced [link to DNA sequencing protocol, include FinchTV as a resource on the page]. With luck, clones with the desired edit are found. Cultures of the edited cells are expanded, some are frozen down [link to cell freezing protocol] for safe keeping, and the rest are used! Gene edited clones can be used for many purposes – to study genetic disease in an ideally controlled cell model, to study effects of non-naturally occurring genetic mutations, to study specific cellular processes or proteins, and to be used therapeutically.